ISSN 2561-2247

The original version was signed by

Kathleen Fox

Chair

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

The original version was signed by

The Honourable Harjit S. Sajjan, PC, OMM, MSM, CD, MP

President of the King’s Privy Council for Canada, Minister of Emergency Preparedness and Minister responsible for the Pacific Economic Development Agency of Canada

From the Chair

Closing the 2022–23 fiscal year marks an opportunity to recognize key achievements from the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB). Our investigation workload continued to grow as transportation volumes returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The past year provided time to refine our hybrid work practices, while keeping our attention fixed on communicating safety messages in all four federally regulated modes of transportation (air, marine, pipeline, and rail). During that time, we released 59 investigation reports, surpassing the previous year’s result of 39 reports. Five of these reports included a total of nine recommendations to drive change in air, marine, and rail sectors:

- In May 2022, we released our investigation report (M20A0160Endnote i) into the 2020 fatal sinking of the small fishing vessel Sarah Anne, off the coast of Newfoundland. The investigation prompted Recommendation (M22-01Endnote ii) for Fisheries and Oceans Canada to require that any Canadian vessel used to commercially harvest marine resources have a current and accurate Transport Canada (TC) registration.

- In August 2022, we released our report (R19W0002Endnote iii) into a 2019 collision between two freight trains near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, in which we issued two recommendations (R22-04Endnote iv, R22-05Endnote v) to TC, one of which builds on outstanding recommendations going back more than two decades. This accident highlighted and reinforced the need for the implementation of physical fail-safe train controls.

- In March 2023, we released our report into the fatal 2021 collision with terrain (A21W0089Endnote vi) of a private aircraft near Lacombe, Alberta. In it we issued a recommendation (A23-01Endnote vii) to TC to routinely review and update the Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners to ensure it contains the most effective screening tools for assessing pilot medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease.

- In the same month, we released our report (M21P0030Endnote viii) into the fatal sinking of the tug Ingenika, including the issuance of four recommendations. The first two recommendations (M23-01Endnote ix, M23-02Endnote x) were addressed to TC to improve and expand regulatory surveillance of tugs under 15 gross tonnage. The other two recommendations (M23-03Endnote xi, M23-04Endnote xii) were to the Pacific Pilotage Authority to address gaps in the issuance of pilotage waivers.

- The investigation into the sinking of the Chief William Saulis (M20A0434Endnote xiii)was the third major investigation released in March of 2023. The Board recommended (M23-05Endnote xiv) that TC ensure that each inspection of a commercial fishing vessel verifies that each required written safety procedure is available to the crew and that the crew are knowledgeable of these procedures.

The TSB continues to drive strong progress in advancing transportation safety through its safety communications.

Since 1990, the Board has made 626 recommendations in all 4 sectors of transport. As of the end of 2022-23, the responses to 83.5% of these had been assessed as Fully Satisfactory. Despite this progress, more timely action is needed in addressing outstanding safety issues.

In further support of advancing transportation safety, October 2022 marked the release of the seventh edition of the TSB Watchlist, which highlights the major safety issues present in air, marine, and rail sectors, and the actions needed to make the Canadian transportation industry even safer.

With a broad-scale return to in-person events, the TSB took part in more than 50 industry events and meetings to discuss important safety issues facing the Canadian transportation sector. These events provide opportunities to share lessons drawn from investigations with transportation industry leaders and personnel and to learn about emerging risks and trends in transportation safety.

I am very proud of the work done by the TSB over the past year. The effort put forward to release investigation reports and to continue to spread the word on safety through our social media and industry outreach initiatives has been substantial. The employees of the TSB continue to put expertise and passion for safety into every project they take on, with demonstrable improvements in the safety of Canada’s transportation system.

Kathleen Fox

Chair

Results at a glance

2022–23 Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) Resource Utilization

- Financial: $36,813,980

- Human: 227 full-time equivalents

- The overall number of accidents across all transportation modes reported in the year 2022 exhibited a 7% increase in comparison to 2021. However, it was 10% below the 10-year average.

- Fatalities in the transportation sector experienced a 5% rise in 2022 when compared to the previous year, 2021. When compared against the 10-year average, there was a 16% reduction.

- In the fiscal year 2022–23, the TSB initiated 50 new investigations, completed 59 investigations, and had 66 investigations in progress at year-end.

- The Board assessed four responses to outstanding recommendations as Fully Satisfactory and issued nine new recommendations in 2022–23, which resulted in an overall total of 83.5% of responses to TSB recommendations being categorized as "Fully Satisfactory."

- During the 2022–23 fiscal year, the TSB completed and released the final reports and recommendations for several significant investigations including: the 2020 fatal sinking of the small fishing vessel Sarah Anne, off the coast of Newfoundland; the fatal 2020 sinking of the fishing vessel Chief William Saulis near Digby, Nova Scotia; the 2019 collision involving two freight trains near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba; the 2021 collision with terrain of a private aircraft near Lacombe, Alberta; and the fatal 2021 sinking of the tug Ingenika in the Gardner Canal, British Columbia. The final reports can be found on the TSB website.

- In October 2022, the TSB published the latest edition of its Watchlist, which continues to highlight key safety issues in the Canadian air, marine, and rail transportation sectors. Realizing that these issues are complex and take time, the Watchlist is moving to a three-year cycle to allow time for meaningful progress to be made by industry and TC.

- Working toward the TSB’s strategic objective of becoming digital by default, we continued implementation of our new project tracking tool to support TSB project tracking, monitoring, searching, and reporting. This new tool will provide a single location for recording project information and a means of standardizing project information across the organization. Also, a segment of the TSB's network drives has been successfully migrated to cloud-based platforms.

- As we move towards a post pandemic environment, the TSB has implemented a hybrid approach and continues to adapt its work arrangements to provide flexibility for in-office and remote work environments.

Results: what we achieved

Core Responsibilities: Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system

Description

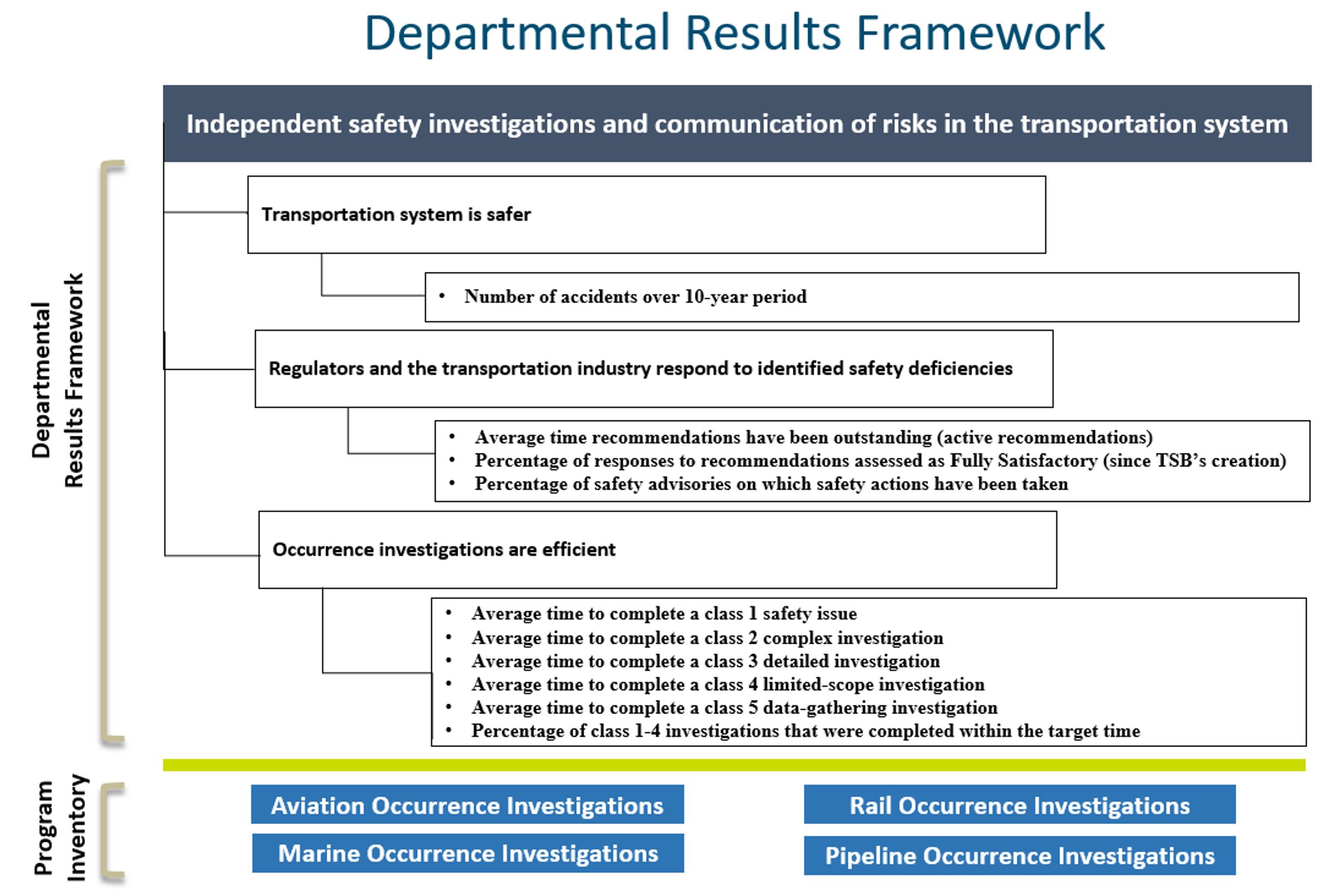

The TSB’s sole objective is to advance air, marine, pipeline and rail transportation safety. This mandate is fulfilled by conducting independent investigations into selected transportation occurrences to identify the causes and contributing factors, and the safety deficiencies evidenced by these occurrences. The TSB makes recommendations to reduce or eliminate any such safety deficiencies and reports publicly on its investigations. The TSB then follows up with stakeholders to ensure that safety actions are taken to reduce risks and improve safety.

Results

The achievement of the TSB’s mandate is measured through three types of departmental result indicators. First, some performance indicators aim at reporting upon the overall safety of the transportation system. However, many variables influence transportation safety, and many organizations play a role in this ultimate outcome. There is no way to directly attribute overall safety improvements to any specific organization. Accident and fatality rates are used as the best available indicators. In recent years, these indicators have generally reflected positive advancements in transportation safety.

The TSB’s departmental results are also measured through actions taken by its stakeholders in response to its safety communications, as well as through efficiency indicators. The TSB must present compelling arguments that convince “agents of change” to take actions in response to identified safety deficiencies. The responses received, the actions taken, and their timeliness are good indicators of the TSB's impact on transportation safety. The TSB actively engages with stakeholders in all modes of transportation. It should be noted that established performance targets and results vary by mode to reflect the different baselines and the differing challenges from one mode to another. These indicators are then consolidated to reflect overall departmental targets and results across all modes of transportation within the TSB’s jurisdiction. Currently, the greatest challenges are with the timeliness of TSB investigation reports.

Organizational priorities

The TSB Strategic Plan outlines the strategic objectives and associated priorities that have been identified by senior management to achieve its strategic outcomes. This plan provides the framework that guides the identification of key activities and the TSB's investment decision making for the current exercise. The progress related to the TSB’s five-year Strategic Plan for the period of 2021–22 to 2025–26 is outlined below.

Strengthen the impact of our investigations

The TSB continued to seek ways to improve how it conducts investigations and to provide credible, transparent, timely, and impactful results that inform and influence the advancement of transportation safety in Canada and abroad. In 2022–23, the TSB carried on with its concerted efforts to improve the quality and timeliness of its investigations. It published a new Policy on Safety Communications and aligned its internal operating procedures and tools accordingly. The TSB also implemented changes to its investigations standards pertaining to the management of investigator powers, the data collection stage of investigations, and the safety analysis.

The TSB continued initiatives aimed at making optimal use of technology to achieve the best possible outcomes with efficient, interconnected, and nimble processes and systems. Efforts continued to develop a new Safety Analysis Tool to support the iterative approach of TSB’s Integrated Safety Investigation Methodology. Processes and guidance materials for class 4 investigations were reviewed and improved. The TSB expanded the use of its Project Tracking Tool implemented at the TSB Laboratory to the Communications Branch.

The TSB remained engaged in the Laboratories Canada program in developing a joint collaborative science facility in partnership with the National Research Council of Canada.Foster an inclusive, diversified and respectful workplace

The TSB is committed to foster a respectful, harassment-free, diversified, and inclusive workplace. In 2022–23, the TSB worked on improving its staffing processes by identifying and removing any barriers to the recruitment, retention and/or promotion of members of designated groups. This included the preparation for implementation of the new PSEA requirements around evaluating staffing tools to identify and mitigate any biases and barriers for equity-seeking groups. The TSB’s Committee on Mental Health in the Workplace has continued to implement and monitor the TSB’s Mental Health Strategy. In addition, the TSB implemented changes to its Critical Incident Stress Management Program, while increasing the amount of resources and tools available to employees. Psychological hazards identified as part of an internal review were incorporated in job safety analyses, and a Psychological Hazards Action Plan has been finalized to address key issues.

The TSB continued its work related to its Strategy on Interactions with Indigenous Peoples. The working group on Interactions with Indigenous Peoples made changes to the TSB’s internal procedures, guidance materials, and resources to improve the organization’s awareness and engagement towards these communities.

Finally, the TSB’s management team has taken concrete action to foster an inclusive workplace in the implementation of the TBS Direction on Prescribed Presence in the Workplace by setting up an EX sub-committee to oversee the exemption and accommodation requests and to provide advice and guidance to the Chief Operating Officer, thus allowing a consistent application of the direction at the TSB.

Employ a knowledgeable and highly skilled workforce

This fiscal year, the TSB continued to focus on the recruitment, development, and retention of a high-performing and diverse workforce. In 2022–23, the TSB ensured that employees could enhance their skills and knowledge through various external and in-house training. In particular, the TSB continued the implementation of its integrated learning management system (LMS365) to facilitate virtual course delivery, course registration, and access to learning records. The organization also redesigned key classroom courses to make learning and knowledge transfer more effective in a virtual environment. In addition, the TSB also conducted an in-depth review of its investigator learning program, to ensure adequate alignment with operational requirements. A learning activities modernization plan was established, and work has begun to redesign and modernize all core TSB training. The organization completed its annual review of its internal policies and procedures, in particular, the Policy on Telework was updated to leverage the maximum flexibility allowable under the new Direction on Prescribed Presence in the Workplace, and the Staffing Policy was updated to reflect the changes in the Public Service Employment Act (PSEA) relating to identifying and mitigating any biases and barriers in staffing tools for equity-seeking groups.

Leverage data to drive our choices and decisions

In 2022–23, the TSB continued the implementation of its Data Strategy to better manage data throughout its life cycle as a shared business asset. The three-phase strategy should be fully implemented by 2025–26. The focus for 2022–23 was on exploring options for improved data architecture and on improving data quality for internal use through updated procedure documentation. The TSB also continued to explore options to support the exchange of data with external stakeholders to create efficiencies and improve the flow of data and information.

Be digital by default

The TSB continued its migration to the cloud. More specifically, the TSB has begun its migration of its server-based SharePoint platform to SharePoint Online, which will be substantially completed in 2023–24. A portion of TSB’s network drives were transferred to the cloud. TSB also ensured that it makes full and effective use of available tools and systems to effectively support employees working remotely and in person.

Communicate with impact

The TSB recognizes that strong, clear communication is essential to ensure investigation findings and key safety messages reach, and are understood by, TSB stakeholders, change agents, and the general public. The TSB recognizes that detailed investigation reports may not suit all audiences; therefore in 2022–23, it continued to strategically tailor the development and delivery of information to target media, stakeholders, and change agents. Furthermore, the TSB continued to leverage its social media channels to reach audiences where they were already communicating.

The TSB proactively engaged its national and international stakeholders through in person engagement opportunities and digital communications platforms to inform them of TSB activities, key safety learnings, and organizational priorities. As well, the department sought opportunities for collaboration to solicit feedback on key safety issues within Canada’s transportation industry and advance its safety messaging to key audiences.

The TSB also recognizes that strong internal communication is crucial for an engaged, well-informed hybrid workforce. As such, the department has continued to leverage existing communication tools such as The Beacon (the TSB’s internal newsletter) and monthly employee townhalls with the Chief Operating Officer as primary sources for important information. The TSB’s intranet site has continued to serve as an important vehicle for communications, knowledge management, and collaboration.Key risks

The TSB recognizes the need for agency-wide integrated risk management practices to effectively manage operations, deliver on its mandate and strategic outcome, and meet central agency expectations. A key element of TSB’s risk management activities is the annual update of its Corporate Risk Profile (CRP). Five key strategic risks have been identified as representing an important threat (or opportunity) to the department:

Keeping up with technological advances/changes in the industry

The TSB’s credibility and operational effectiveness could be impacted if it fails to keep pace with the technological advances/changes in the transportation industry and if it does not adapt to ensure new data sources are properly exploited, optimally managed, and fully analyzed. New advances in engineering, designs, and operational systems occur at times faster than the organization can adapt. Some examples of technological change that could pose challenges to the TSB’s work are increased automation in some transportation sectors and remotely piloted vehicles being integrated into existing transportation systems. To be able to properly access public and private data for investigations, additional efforts will be required for TSB employees to maintain or acquire the requisite expertise and have access to the equipment and training necessary to conduct transportation occurrence investigations in the future. To this end, the TSB continues with its data strategy implementation. Investments were also made to procure new lab equipment to address advances in the industry. Investigator competencies development framework was also reviewed.

Keeping up with workplace technology

There is a risk that TSB employees do not have access to current workplace technology tools, systems, and applications to ensure they can deliver their work in an efficient and effective manner. As a world-class investigative organization, it is important that employees are equipped with the latest technology tools/software/hardware to be able to interact with OGDs, stakeholders, other investigation organizations and industry. As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a strong need to ensure that these tools are not subject to business disruptions by third parties or other events. To this end, TSB continued the implementation of its IM/IT vision. A portion of TSB’s network drives were transferred to the cloud. Further network access improvements were implemented.

Employee safety and wellbeing

There is a need to be vigilant with respect to managing employee physical and mental wellbeing and maintaining a work environment that is supportive, respectful, diverse, and free of harassment. Due to the nature of the work performed by the TSB, employees may be exposed to a number of physical and psychological hazards. To this end, following a 3-year pilot project, TSB implemented changes to its Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) Directive, and Program, by streamlining the way the program is administered, improving tools and learning activities, and making more resources available to staff in relations to CISM. A Psychological Hazards Action Plan was also implemented over the year and actions were taken to significantly reduce and mitigate psychological risks encountered by staff during the course of investigations. Also, the Committee on Mental Health in the Workplace continued its efforts to implement the TSB’s Mental Health Strategy to foster a supportive, respectful, and stigma-free workplace that promotes and supports the mental health and wellbeing of all TSB employees.

Operational responsiveness

There is a risk that the TSB may not be able to deploy in a timely manner, and to sustain operations, in certain remote regions due to the limited availability of transportation services and support infrastructure. There is also a risk that investigation deployment contingency plans will not be robust enough and sufficiently practised to ensure a proper state of readiness. To this end, in March 2023, the TSB participated in a multi-departmental major maritime accident tabletop exercise in Charlottetown PEI. The “Safe Return 2023” was a multiday facilitated discussion exercise which took participants through the process of dealing with a simulated disaster scenario from their organization's point of view. Lessons learned will be used to direct further work on the matter.

Legal challenges

Organizations and individuals are more frequently challenging TSB business processes, as well as the application of the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (CTAISB Act). This puts the TSB at risk that some court rulings could negatively impact the way the TSB conducts its business. In 2022–23, the General Counsel for the TSB continued to uphold the TSB’s legal position pursuant to the CTAISB Act in court proceedings throughout the year in order to preserve the TSB’s investigative integrity. The General Counsel for the TSB also provided regular information sessions on pertinent legal matters to all TSB employees.

Results achieved

The following table shows, for independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system, the results achieved, the performance indicators, the targets, and the target dates for 2022–23, and the actual results for the three most recent fiscal years for which actual results are available.

Notes about the indicators

The TSB amended its Departmental Results Framework (DRF) at the Departmental Results Indicator (DRI) level effective 2022–23 as a result of a thorough review that identified several opportunities to streamline Results data in order to provide more valuable and concise information to the public and its stakeholders. The resulting DRI structure consolidates previous departmental indicators into new indicators, which explains why no comparative data is available in the table below. Note that all previous years’ data remains fully accessible through the TSB website as well as GC InfoBase. Additionally, the TSB will continue to report further departmental statistics as part of its Annual Report to Parliament.

| Departmental results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2020–21 actual results | 2021–22 actual results | 2022–23 actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation system is safer | Number of accidents over 10-year period | Reduction in number of accidents | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Met The number of accidents in 2022 was 1,402, lower than the prior 10-year average of 1,555. |

| Regulators and the transportation industry respond to identified safety deficiencies | Average time recommendations have been outstanding (active recommendations) | 8 years | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met 10.8 years. Note that the mean time open has declined from more than 13 years. |

| Regulators and the transportation industry respond to identified safety deficiencies | Percentage of responses to recommendations assessed as Fully Satisfactory (since TSB’s creation) | 1.5% increase from previous fiscal year result | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met -1% Decrease from last year’s level of 84.5% to 83.5% this year. Note that this indicator is lower because the TSB has issued new recommendations, which have not yet received a fully satisfactory response. |

| Regulators and the transportation industry respond to identified safety deficiencies | Percentage of safety advisories on which safety actions have been taken | 60% | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met Safety actions were taken on 46% of the safety advisories that were issued. |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time to complete a class 1 safety issue investigation | 730 days | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time to complete a class 2 complex investigation | 600 days | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met 1,143 days |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time to complete a class 3 detailed investigation | 450 days | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met 611 days |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time to complete a class 4 limited-scope investigation | 220 days | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met 235 days |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time to complete a class 5 data-gathering investigation | 60 days | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Met 56 days |

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Percentage of class 1-4 investigations that were completed within the target time | 60% | March 2023 | N/A | N/A | Not met 32% 19 of 59 investigations completed within the target time. |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.Endnote xv

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

The following table shows, for independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system, budgetary spending for 2022–23, as well as actual spending for that year.

| 2022–23 Main Estimates | 2022–23 planned spending | 2022–23 total authorities available for use | 2022–23 actual spending (authorities used) | 2022–23 difference (actual spending minus planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28,609,026 | 28,609,026 | 28,935,952 | 27,886,696 | (722,330) |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.Endnote xvi

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

The following table shows, in full-time equivalents, the human resources the department needed to fulfill this core responsibility for 2022–23.

| 2022–23 planned full-time equivalents | 2022–23 actual full-time equivalents | 2022–23 difference (actual full-time equivalents minus planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 177 | 176 | (1) |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.Endnote xvii

Internal services

Description

Internal services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support program delivery in the organization, regardless of the internal services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are:

- acquisition management services

- communication services

- financial management services

- human resources management services

- information management services

- information technology services

- legal services

- material management services

- management and oversight services

- real property management services

The Internal Services program continued to strive to ensure that the TSB makes full and effective use of available tools and systems to support working in a digital-first hybrid environment.

We continued our migration to the cloud to ensure employees have efficient access to workplace technology, whether they are working in our facilities or remotely. We began the migration of our server-based SharePoint platform to SharePoint online (cloud) which will be substantially completed in 2023–24. A portion of TSB’s network drives were transferred to the cloud. We further improved our network access and expanded the use of our project tracking tool to the Communications Branch.

We maintained our logistical support to the department and its employees in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We made additional investments to improve our hybrid work environment in line with the Direction on Prescribed Presence in the Workplace. This strengthened our position as an employer of choice by providing ongoing support for the health and wellbeing of our employees.

We prepared and published our first Accessibility Plan in December 2022.

The TSB’s Finance division continued to work in collaboration with its HR division and Public Services and Procurement Canada compensation personnel to ensure that Phoenix issues were minimized and employees were paid in a timely manner. Where appropriate, cash advances were issued to employees.

Additionally, Internal Services personnel also worked on other initiatives that support employee wellbeing including responding to the results of the annual Public Service Employee Survey, the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service, mental health, and other activities aimed at furthering diversity and inclusion.

Other activities included supporting the implementation of our Data Strategy Plan focusing on foundation elements such as a review of our data architecture and efforts to improve data quality.

Since 2018 we have also been pursuing the realization of a project for the modernization of the TSB Engineering Laboratory facility, which was built in 1980. These efforts, in partnership with the National Research Council, and as part of the Laboratories Canada program within Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), are expected to provide our employees with a renewed and highly functional work environment that promotes efficiency, scientific collaboration, and innovation. As this initiative requires investment and on-going maintenance funding that is beyond our current appropriations (budget), we will continue to engage with PSPC and central agencies to bring the project to a successful conclusion.

Contracts awarded to Indigenous businesses

The TSB is a Phase 1 department and as such must ensure that a minimum 5% of the total value of the contracts it awards go to Indigenous businesses by the end of 2022–23. In its 2023–24 Departmental Plan, the department forecasted that, by the end of 2022–23, it would award 9.7% of the total value of its contracts to Indigenous businesses.

As shown in the following table, the TSB awarded 11.6% of the total value of its contracts to Indigenous businesses in 2022–23.

| Contracting performance indicators | 2022–23 Results |

|---|---|

| Total value of contracts* awarded to Indigenous businesses† (A) | $245,716 |

| Total value of contracts awarded to Indigenous and non-Indigenous businesses‡ (B) | $2,117,941 |

| Value of exceptions approved by deputy head (C) | $0 |

| Proportion of contracts awarded to Indigenous businesses [A / (B−C) × 100] | 11.6% |

* Includes contract amendments with Indigenous businesses and contracts that were entered into with Indigenous businesses by means of acquisition cards. May include subcontracts.

† For the purposes of the 5% target, Indigenous businesses include Elders, band and tribal councils; businesses registered in the Indigenous Business Directory for contracts under the Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Business; and businesses registered in a beneficiary business list for contracts with a final delivery in a modern treaty or self-government agreement area with economic measures as defined by Indigenous Services Canada.

‡ Includes contract amendments.

In fiscal year 2022–23, the TSB exceeded its projected contract value awarded to Indigenous Businesses of 9.7% by 1.9%, surpassing the minimum target of 5%. This achievement can be attributed to the TSB's decision to entrust most office furniture contracts to Indigenous vendors as part of its hybrid workplace project, along with its continued commitment to Indigenous contractors in various IT initiatives.

To promote greater consideration of Indigenous businesses within the organization, the TSB contracting team initiated an awareness-raising campaign among internal clients. This campaign encouraged them to propose Indigenous businesses for goods and services requests, whenever market capacity permitted. To facilitate this, the TSB contracting team leveraged the CPSS tool and primarily targeted Indigenous businesses.

Furthermore, the TSB enhanced the client request form to incorporate Indigenous business considerations, along with a convenient direct link to the Indigenous business directory. In addition, all procurement employees have successfully completed two crucial courses provided by the Canada School of Public Service:

- Indigenous Considerations in Procurement (COR409)

- Procurement in the Nunavut Settlement Area (COR410)

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

The following table shows, for internal services, budgetary spending for 2022–23, as well as spending for that year.

| 2022–23 Main Estimates | 2022–23 planned spending | 2022–23 total authorities available for use | 2022–23 actual spending (authorities used) | 2022–23 difference (actual spending minus planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7,152,256 | 7,152,256 | 9,263,180 | 8,927,284 | 1,775,028 |

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

The following table shows, in full-time equivalents, the human resources the department needed to carry out its internal services for 2022–23.

| 2022–23 planned full-time equivalents | 2022–23 actual full-time equivalents | 2022–23 difference (actual full-time equivalents minus planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 51 | 1 |

Spending and human resources

Spending

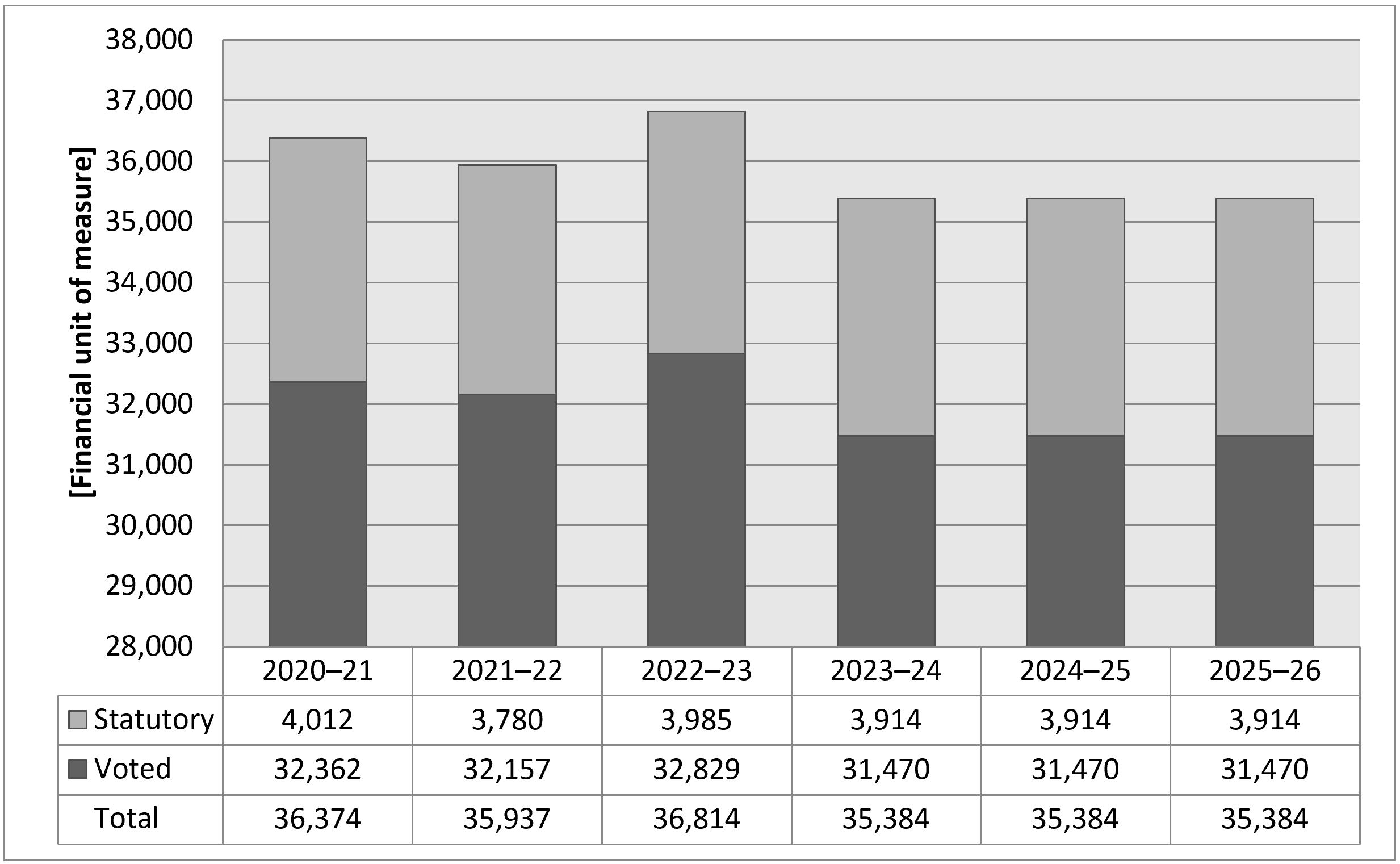

Spending 2020–21 to 2025–26

The following graph presents planned (voted and statutory spending) over time.

The departmental spending trend graph shows actual spending (2020–21 to 2022–23) and planned spending (2023–24 to 2025–26). The variation in statutory amounts over the years is directly attributable to Employee Benefit Plan allocations associated to employee salaries. Further trend analysis related to this table is provided in the following section.

Budgetary performance summary for core responsibilities and internal services (dollars)

The table below, Budgetary performance summary for core responsibilities and internal services, presents the budgetary financial resources allocated for the TSB’s core responsibilities and for internal services.

| Core responsibilities and internal services | 2022–23 Main Estimates | 2022–23 planned spending | 2023–24 planned spending | 2024–25 planned spending | 2022–23 total authorities available for use | 2020–21 actual spending (authorities used) | 2021–22 actual spending (authorities used) | 2022–23 actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system | 28,609,026 | 28,609,026 | 28,306,923 | 28,306,923 | 28,935,952 | 28,397,258 | 27,655,335 | 27,886,696 |

| Internal services | 7,152,256 | 7,152,256 | 7,076,731 | 7,076,731 | 9,263,180 | 7,976,504 | 8,281,582 | 8,927,284 |

| Total | 35,761,282 | 35,761,282 | 35,383,654 | 35,383,654 | 38,199,132 | 36,373,762 | 35,936,917 | 36,813,980 |

The 2020–21 to 2022–23 actual spending results are actual amounts as published in the Public Accounts of Canada. The increase in actual spending during the fiscal year 2022–23 can be primarily attributed to a rise in travel related expenses explained by the resumption of typical activities following the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The significant increase of $2.4M between 2022–23 planned spending and 2022–23 total authorities available for use is explained by the additional authorities the TSB received throughout the fiscal year:

- $1.5M for its operating budget carry forward from 2021–22

- $0.6M as a result of its Memorandum of Understanding with Laboratories Canada

- $0.2M for compensation allocations and funding to cover mandatory cash-outs for vacation and compensatory leave

The remaining $0.1M is a combination of other authorities in lesser amounts but is mainly comprised of the gains from the sale of capital assets, cost recovery of an investigation, and the annual employee benefit plan (EBP) rate adjustment set by Treasury Board Secretariat.

In accordance with the definition of planned spending, planned amounts for 2023–24 and ongoing fiscal years are comprised of Main Estimates and Annual Reference Level amounts only. These amounts remain consistent over the planning horizon based on the information available at the time of preparation. Future spending may be influenced by government mandated decisions, however this impact is not yet known.

Human resources

The “Human resources summary for core responsibilities and internal services” table presents the full-time equivalents (FTEs) allocated to each of the TSB’s core responsibilities and to internal services.

Human resources summary for core responsibilities and internal services

| Core responsibilities and internal services | 2020–21 actual full-time equivalents | 2021–22 actual full-time equivalents | 2022–23 planned full-time equivalents | 2022–23 actual full-time equivalents | 2023–24 planned full-time equivalents | 2025–25 planned full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system | 174 | 179 | 177 | 176 | 177 | 177 |

| Internal services | 50 | 47 | 50 | 51 | 50 | 50 |

| Total | 224 | 226 | 227 | 227 | 227 | 227 |

In 2022–23, the TSB continued to staff and fill vacancies and as a result, the 2022–23 actual figures were exactly as planned. The TSB anticipates FTEs to remain consistent for 2023–24 and onward at 227 FTEs.

Expenditures by vote

For information on the TSB’s organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada.Endnote xviii

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of the TSB’s spending with Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available in GC InfoBase.Endnote xix

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The TSB’s financial statements (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2023,Endnote xx are available on the department’s website.

Financial statement highlights

Condensed Statement of Operations (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2023 (thousands of dollars)

| Financial information | 2022–23 planned results | 2022–23 actual results | 2021–22 actual results | Difference (2022–23 actual results minus 2022–23 planned results) | Difference (2022–23 actual results minus 2021–22 actual results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 39,514 | 41,866 | 40,166 | 2,352 | 1,700 |

| Total revenues | 19 | 112 | 16 | 93 | 96 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | 39,495 | 41,754 | 40,150 | 2,259 | 1,604 |

The 2022–23 planned results information is provided in the TSB’s Future-Oriented Statement of Operations and Notes 2022–23.Endnote xxi

Planned results for the fiscal year 2022–23 are based on estimates known at the time of preparation of the Future-Oriented Financial Statements, an integral component of the 2022–23 Departmental Plan. These estimations were made based on the information accessible at that point in time. Subsequently, the planned results of $39.5M and the actual expenditure of $41.8 million resulted in a variance of $2.3M or 5.5%.

On an accrual accounting basis, the TSB’s total operating expenses for 2022–23 are $41.8M, representing an increase of $1.6M compared to the previous fiscal year's total of $40.2M. Salary expenses remained consistent across both fiscal years, with the variance arising from a substantial increase in operating expenses, resulting in a significant year-over-year difference. The most notable increases were, as expected in a post-pandemic year with a return to normal activities, in the transportation and communications category, as well as a significant increase in the provision for expired collective agreements.

The TSB’s revenues are incidental and result from cost recovery from investigation activities, as well as the rebate received from its supplier for the use of its TSB acquisition cards in 2022–23.

Condensed Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) as of March 31, 2023 (thousands of dollars)

| Financial information | 2022–23 | 2021–22 | Difference (2022–23 minus 2021–22) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 7,255 | 6,632 | 623 |

| Total net financial assets | 2,391 | 2,584 | (193) |

| Departmental net debt | 4,864 | 4,048 | 816 |

| Total non-financial assets | 6,570 | 6,343 | 227 |

| Departmental net financial position | 1,706 | 2,295 | (589) |

The 2022–23 planned results information is provided in the TSB’s Future-Oriented Statement of Operations and Notes 2022–23.Endnote xxii

The TSB’s total net liabilities consist primarily of accounts payable and accrued liabilities relating to operations, which account for $4.2M or 58% (48% in 2021–22), and vacation pay and compensatory leave, which account for $2.3M or 32% (41% in 2021–22) of total liabilities. The liability for employee future benefits pertaining to severance pay represents $0.7M or 9% (12% in 2021–22) of total liabilities. The overall increase in net liabilities between years is primarily attributed to allowances for expired collective agreements for all TSB classifications except for the Financial Management (FI) group. Offsetting this increase is the payout of excess vacation throughout the fiscal year following the lifting of the moratorium on mandatory cash out of excess vacation and compensatory leave, which took effect last year.

Total net financial assets consist of accounts receivable, advances, and amounts due from the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) of the Government of Canada. The amount due from the CRF represents 97% or $2.3M (94% in 2021–22) of the year-end balance, a decrease of $0.1M. This represents a reduction in the amount of net cash that the TSB is entitled to draw from the CRF in the future to discharge its current liabilities without further appropriations. The TSB’s total net financial assets have decreased by $0.2M attributable to the lower amount due from the CRF, in addition to a reduction in accounts receivable.

Total non-financial assets consist primarily of tangible capital assets, which make up $6.4M or 98% of the balance (98% in 2021–22), with inventory and prepaid expenses accounting for the remaining 2%. The increase of $0.2M in non-financial assets between years is mainly due to the increase in prepaid expenses ($0.1M) and acquisition of new assets ($1.4M) offset by the annual amortization ($1.3M).

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Appropriate minister:The Honourable Harjit S. Sajjan, PC, OMM, MSM, CD, MP

Institutional head: Kathleen Fox

Ministerial portfolio: Privy Council

Enabling instrument: Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board ActEndnote xxiii,S.C. 1989, c. 3Endnote xxiv

Year of incorporation / commencement: 1990

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

“Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do” is available on the TSB’s website.Endnote xxv

Operating context

Information on the operating context is available on the TSB’s website.Endnote xxvi

Reporting framework

The TSB’s departmental results framework and program inventory of record for 2022–23 are shown below.

Supporting information on the program inventory

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.Endnote xxvii

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the TSB’s website:

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures.Endnote xxx This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs as well as evaluations and GBA Plus of tax expenditures.

Organizational contact information

Mailing address:

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Place du Centre, 4th floor

200 Promenade du Portage

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1K8

Telephone: 1-800-387-3557

Email: communications@tsb-bst.gc.caEndnote xxxi

Website: www.tsb.gc.caEndnote xxxii

Appendix: definitions

appropriation (crédit)

Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

core responsibility(responsabilité essentielle)

An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a core responsibility are reflected in one or more related departmental results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

Departmental Plan (plan ministériel)

A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a 3-year period. Departmental Plans are usually tabled in Parliament each spring.

departmental priority (priorité)

A plan or project that a department has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired departmental results.

departmental result (résultat ministériel)

A consequence or outcome that a department seeks to achieve. A departmental result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

departmental result indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

A quantitative measure of progress on a departmental result.

departmental results framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

A framework that connects the department’s core responsibilities to its departmental results and departmental result indicators.

Departmental Results Report (rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

A report on a department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

full-time equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person-year charge against a departmental budget. For a particular position, the full-time equivalent figure is the ratio of number of hours the person actually works divided by the standard number of hours set out in the person’s collective agreement.

gender-based analysis plus (GBA Plus) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS Plus])

An analytical tool used to support the development of responsive and inclusive policies, programs and other initiatives; and understand how factors such as sex, race, national and ethnic origin, Indigenous origin or identity, age, sexual orientation, socio-economic conditions, geography, culture and disability, impact experiences and outcomes, and can affect access to and experience of government programs.

government-wide priorities (priorités pangouvernementales)

For the purpose of the 2022–23 Departmental Results Report, government-wide priorities are the high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the November 23, 2021, Speech from the Throne: building a healthier today and tomorrow; growing a more resilient economy; bolder climate action; fighter harder for safer communities; standing up for diversity and inclusion; moving faster on the path to reconciliation; and fighting for a secure, just and equitable world.

horizontal initiative (initiative horizontale)

An initiative where two or more federal organizations are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

non-budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

performance (rendement)

What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

performance indicator (indicateur de rendement)

A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

performance reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement)

The process of communicating evidence-based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

plan (plan)

The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally, a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead to the expected result.

planned spending (dépenses prévues)

For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts presented in Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports.

program (programme)

Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

program inventory (répertoire des programmes)

Identifies all the department’s programs and describes how resources are organized to contribute to the department’s core responsibilities and results.

result (résultat)

A consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

Indigenous business (enterprise autochtones)

For the purpose of the Directive on the Management of Procurement Appendix E: Mandatory Procedures for Contracts Awarded to Indigenous Businesses and the Government of Canada’s commitment that a mandatory minimum target of 5% of the total value of contracts is awarded to Indigenous businesses, an organization that meets the definition and requirements as defined by the Indigenous Business Directory.

statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives)

Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

target (cible)

A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

voted expenditures (dépenses votées)

Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an appropriation act. The vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.